The good news is you’re cancer free, the bad news is you need a heart transplant.

It almost sounds like the punchline to a joke, but it’s no laugher matter because the scenario is real for some cancer patients. Chemotherapy is a life saver for many but certain doses can be so toxic that it’s often hard to tell which symptoms are due to the cancer and which are due to the drug. Doxorubicin, used to treat around 50% of people diagnosed with breast cancer, is particularly awful. It’s been estimated that about 8% of those treated with doxorubicin experience side effects to the heart with symptoms ranging from arrhythmias to congestive heart failure severe enough to require heart transplantation.

doxorubicin, a chemotherapy drug that carries a risk of serious heart damage

Avoiding the fire after jumping out of the frying pan

To avoid this predicament, doctors need a way to screen for an increased risk of heart damage due to doxorubicin before a patient even sets foot in a chemotherapy clinic. A CIRM-funded Stanford research team has made a big step toward that goal. Reporting yesterday in Nature Medicine, the scientists describe a non-invasive laboratory method that could help pinpoint which breast cancer patients are most likely to experience so-called doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity, or DIC.

Eight woman with breast cancer who had received doxorubicin treatment were recruited for the study. Four suffered from DIC while the other four did not. Skin samples were obtained from each person as well as four healthy volunteers. In the lab, the skin fibroblasts were reprogrammed into embryonic-like induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS) and then specialized into beating heart muscle cells or cardiomyocytes.

Chemo-induced heart damage in a dish

To find out if these patient-derived heart cells in the lab reflect what happened inside the patients’ hearts, the team compared the effects of doxorubicin on the different groups of cells. Looking at cell survival and the rhythmic beating of the heart cells, differences emerged. Lead author Paul Burridge summarized the results in a university press release:

“We found that cells from the patients who had experienced doxorubicin toxicity responded more negatively to the presence of the drug. They beat more irregularly in response to increased levels of doxorubicin, and we saw a significant increase in cell death after 72 hours of exposure to the drug when we compared those cells to cells from healthy controls or patients who didn’t have heart damage.”

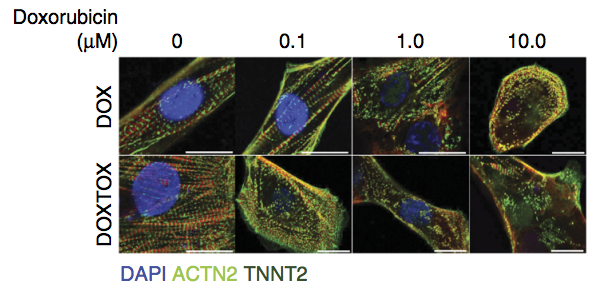

iPS-derived heart muscle cells from patients without (DOX, first row) and with (DOXTOX, bottom row) doxorubicin toxicity were treated with increasing amounts of the doxorubicin. The regular green stripe patterns indicate normal, intact muscle structures. By 0.1 µM of drug (second column), the DOXTOX structures become disarrayed while the DOX cells remain intact. Image: Burridge et al. Nat Med. 2016 Apr 18.

So how exactly does doxorubicin wreak havoc on the heart and why are some patients more sensitive to the drug?

Feeling the burn of reactive oxygen species (ROS)

The answers, in part, lie inside cellular structures called mitochondria where calories, stored in the form of sugar and fat, are “burned” to generate the body’s energy needs. A harmful byproduct of this energy metabolism is reactive oxygen species (ROS), a chemically reactive form of oxygen that damages the mitochondria and other cell components. This damage is especially bad for heart cells which are 35% mitochondria by volume due to their intense energy needs as they busily beat for a lifetime.

Now, earlier research studies had pointed to ROS production in mitochondria as a key deliverer of doxorubicin’s destructive effects on the hearts of chemotherapy patients. So the Stanford team investigated the drug’s effects on ROS production and on mitochondria function in context of their patient derived heart cells. In response to doxorubicin, the scientists found that the cells from patients with doxorubicin induced heart damage generated more ROS compared to the cells from patients who had no heart damage. Along with the higher ROS production, mitochondria function was more compromised in the doxorubicin-sensitive heart cells.

And even in the absence of treatment, there was a lower baseline function and quantity of mitochondria in the doxorubicin-sensitive cells. These results suggest some underlying genetic differences in the heart muscle cells of patients with DIC. The team plans to perform DNA comparisons to pinpoint the genes involved and ultimately help patients survive cancer without the fear of swapping it for another life threatening illness.

iPS cells: opening new paths for helping cancers patients

Compared to tools he had previously relied on, Joseph Wu, the team leader and director of the Stanford’s Cardiovascular Institute, is very excited about his lab’s future research possibilities:

“In the past, we’ve tried to model this doxorubicin toxicity in mice by exposing them to the drug and then removing the heart for study. Now we can continue our studies in human cells with iPS-derived heart muscle cells from real patients. One day we may even be able to predict who is likely to get into trouble.”